Migration acts as an escape valve for conflict in areas suffering from climate change, but does not increase conflict in destination countries

By reducing agricultural productivity, and worsening living conditions, climate change and in particular rising temperatures may force individuals to move out of rural and hot areas into places with a cooler climate. Migration is an important margin of adaptation to these climatic changes. The possibility of people moving to other countries may reduce the costs of climate change by attenuating some of its negative consequences. In particular, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have experienced in recent decades civil conflicts for which droughts and temperature increases have been identified as major drivers (Burke et al. 2009). International migration can reduce the risk of conflicts connected to climate change and scarcity of resources in origin countries.

Tensions in destination countries

On the other hand, increased flows of climate migrants affect destination countries. Demographic and economic pressure brought by the new arrivals in the receiving countries may trigger ethnic and cultural tensions, which could generate new conflicts or fuel existing ones. The pressure on available resources could be exacerbated if language barriers and cultural differences make the interaction between locals and immigrants difficult. The environmental conflict model (Homer-Dixon 2001) postulates that migration induced by environmental factors will strain scarce resources in destination countries and become a primary source of instability. The latest IPCC assessment report (IPCC 2014), the OECD outlook on migrations (OECD 2016), and the World Bank (Bougnoux et al. 2014), among other international institutions, have stressed the role that climate migrants could potentially play on social stability in future decades.

The triple connection: Are climate, migration, and conflict connected to one another?

Climate-induced migration may be an escape valve in the areas of origin and a possible driver of social unrest in the areas of destination. In a recent paper (Bosetti et al. 2018), we investigate the triple connection between climate, conflict, and migration from two possible perspectives: the origin and the destination areas. To do this we use a panel of country-level data on climate, civil conflict, emigration and immigration, encompassing 126 countries over a period of 40 years from 1960 to 2000. Our identification approach uses climate change as the exogenous push factor, and the presence of historical migrant networks (in the form of pre-existing diaspora of migrants as of 1960, the beginning of the period under analysis) as an indicator of ‘propensity to emigrate’ from a specific country.

The diaspora would facilitate emigration for a series of reasons. First, the existence of a large network of nationals abroad reduces the costs of moving and increases the information available to perspective emigrants, increasing the probability that they respond to migration incentives. Second, there are often family ties between the diaspora and people in the country of origin. Many developed countries select a large proportion of immigrants on the basis of family reunification, hence this creates an easier channel of migration. Finally, the diaspora variable proxies for how likely emigration was in the past, capturing some of the potential barriers to emigration that are specific to a given country of origin and likely to persist.

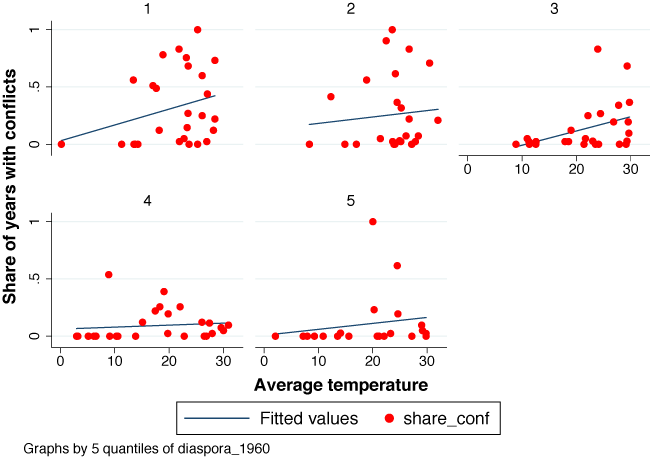

The five panels of Figure 1 illustrate the key feature of the correlation between temperature and conflict, as the intensity of country’s diaspora varies. The top three panels show those countries with diaspora in the lower three quintiles, the bottom two panels show countries with diaspora in the top two quintiles. We can see a positive and significant relationship between temperature and conflict frequency among countries with small diaspora levels (top three panels), but a much lower correlation is visible for countries with larger diaspora levels (bottom two panels).

Figure 1 Correlation between temperature and conflict, by intensity of diaspora

Warming, diaspora, and conflict in the countries of origin

To systematically assess this relationship between climate, conflict, and migration in origin and destination countries, we perform regression analyses using different approaches and specifications. As far as origin countries are concerned, we first confirm that warming increases the risk of civil conflict in poor countries, while it has a negligible and not statistically significant effect in rich and middle-income countries. Then we show that in poor countries with low diaspora (those in the bottom quartile of the diaspora variable), the effect is much stronger. An increase in temperature by one degree Celsius increases the risk of conflict by up to 17 percentage points in low diaspora countries and by only 7 percentage points in high diaspora countries. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that, for poor countries, ease of emigration attenuates the effect of climate change on the risk of conflict.

Climate-driven migration and conflict in the countries of destination

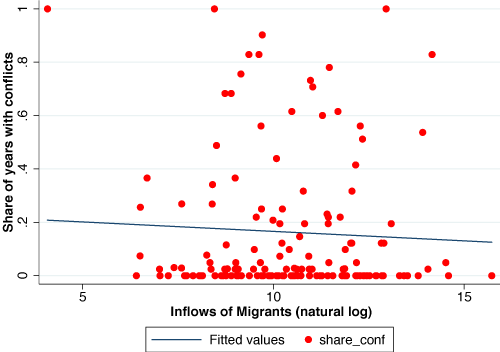

Emigration seems to act as an effective valve to dissipate possible conflict following years of high average temperatures. It is natural, therefore, to ask whether this happens at the expense of increasing the risk of conflict in the receiving countries, which may be pressured or overwhelmed by climate-induced migrants. While only a correlation, Figure 2 suggests no clear association between total immigration flows and the presence of civil conflict. To test more formally whether climate migrants have an effect on conflict in receiving countries, we construct a measure of climate-driven migrants through a ‘gravity’ approach that predicts bilateral migrants based on a variety of origin-destination characteristics and on bilateral temperature differentials. We find that people migrating because of variation in temperature differences between countries do not represent a significant driver of conflict in destination countries. Taken together, the two results suggest that migration acts as an escape valve, reducing conflict generated by climate change in countries of origin, and at the same time does not significantly increase the risk of conflict in the receiving countries.

Figure 2 Correlation between immigration and conflict, 1960-2000

Conclusions

Most of our findings are consistent with emigration reducing the negative effect of climate change on conflicts in origin countries. This finding supports the idea of migration as a mechanism of adaptation and conflict mitigation (Black et al. 2011, Hartmann 2010). The result is particularly critical for poor countries, where warming is associated with a higher risk of civil conflict. At the same time, we find no statistically significant effect of climate migrants on conflicts in countries of destination. These findings suggest an important and positive role for international migrations in diffusing climate-induced conflict. They also undermine the hypotheses of the environmental conflict model (Homer-Dixon 2001) and the degradation narratives claiming that migrants induced by environmental factors strain scarce resources in destination countries and become a primary source of instability (Collier and Hoeffler 2004).

References

Black, R, S Bennett, S Thomas, and J Beddington (2011), “Climate change: Migration as adaptation.” Nature 478 (7370): 447–49.

Bosetti, V, C Cattaneo and G Peri (2018), “Should they stay or should they go? Climate migrants and local conflicts.” NBER Working Paper 24447.

Bougnoux, N, G Joseph, Q Wodon and A Liverani (2014), “Climate change and migration : Evidence from the Middle East and North Africa.” A World Bank Study.

Burke, M, E Miguel, S Satyanath, J Dykema and D Lobell (2009), “Warming increases the risk of civil war in Africa.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(49): 20670–74.

Collier, P and A Hoeffler (2004), “Greed and grievance in civil war.” Oxford Economic Papers 56(4): 563–95.

Hartmann, B (2010), “Rethinking climate refugees and climate conflict: Rhetoric, reality and the politics of policy discourse.” Journal of International Development 22(2): 233–46.

Homer-Dixon, T (2001), Environment, scarcity, and violence, Reprint edizione, Princeton Univ Press

IPCC (2014), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

OECD (2016), International migration outlook 2016.